Introduction

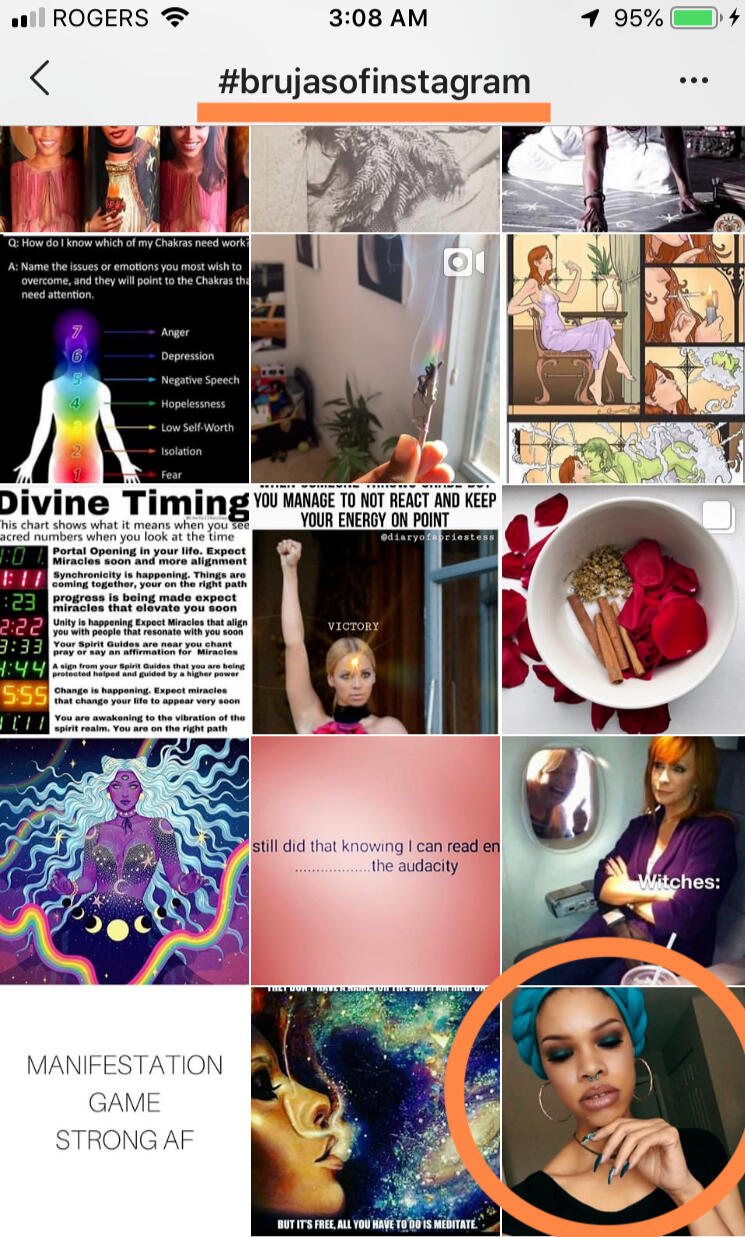

Several years ago, I came across a vibrant online community of people who identify as witches and use their Instagram profiles to promote their witch-oriented businesses and skill sets. It is through Instagram that these witches perform the unique ability to promote their shared ideologies as activists along with their products and services as online entrepreneurs. While examining the broad diversity of this community, however, I soon recognized a paradoxical trend in how these entrepreneurs are represented through Instagram. While this community consists of people of various gender identities, sexual orientations, ethnicities, etc., I soon recognized that popular hashtag feeds that represent this community do not adequately represent its diversity; nor do these feeds adequately represent the conscious sociopolitical spirit of this community. It is through this digital project that I analyze these concerns, potential causes behind these misrepresentations, and further considerations for future related research.This digital research project has been cultivated through utilizing discourse analysis and a variety of online ethnographic research methods. While conducting online ethnographic research for this project, I focused primarily on American witch entrepreneurs who use the popular hashtag, #witchesofinstagram, to promote their Instagram posts. I have been closely examining Instagram posts that maintain this hashtag but were not algorithmically selected for display on the #witchesofinstagram hashtag feed. I will further elaborate upon hashtag feeds and their importance to communal representation in the section entitled, “Algorithmic Homogeneity”.While examining eligible Instagram posts that were not featured/displayed through the #witchesofinstagram hashtag feed, I also analyzed the hashtag feeds of other similar popular hashtags such as #witch and #brujasofinstagram—bruja being a Spanish term used to describe mostly female Latin-American witches. I will further examine eligible Instagram posts in relation to several popular witch-themed hashtags in “Algorithmic Homogeneity”. I was inspired to examine additional popular witch-themed hashtags and the curation of their respective feeds since many of the Instagram posts I observed also typically included other popular related hashtags such as #witch and #brujasofinstagram.

A Brief Historical Overview of Witches in the United States of America

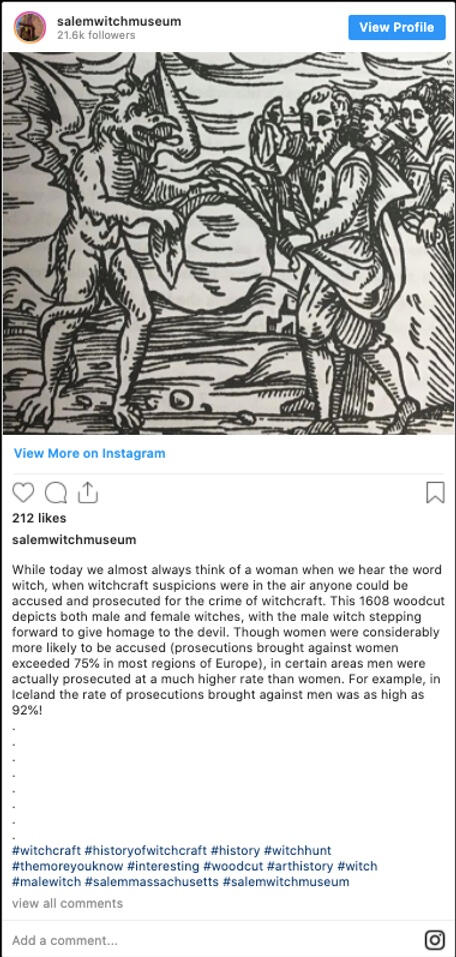

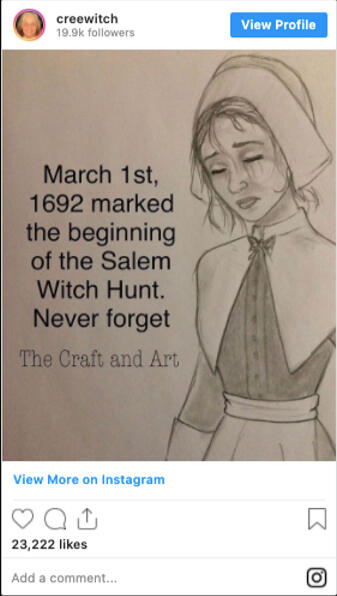

To understand this movement's foci on socially conscious entrepreneurship and community building, it is significant to understand a (very) brief history of where witches have existed throughout history. For the specific purposes of this project, I focus predominantly on Western European and American history. As Kristen J. Sollée (2017) notes, witch hunts and witch trials were prevalent during the sixteenth century throughout parts of Western Europe including the Netherlands and England. These trials and hunts were also popular in the United States throughout the seventeenth century; this was observed through the infamous Salem Witch Trials of Salem, Massachusetts (2017). People who did not identify as witches were tortured and killed based on a variety of different accusations and causes that ranged from being folk healers to potentially defying societal sexuality norms (2017).Female midwives were in especially precarious positions since many were often tried as witches or responsible for accusing supposed witches as a means of socially proving their own unwavering devotion to the Catholic church (Federici 2004; Sollée 2017). What has been especially noted by Silvia Federici (2004) regarding these trials and hunts is a trend that correlates the overwhelming number of women being persecuted as witches with the increased normalization of two predominant patriarchal, capitalistic trends. One of these trends involved the removal of women from positions of power related to women’s health and well-being. This occurred as men gradually replaced midwives as midwifery became increasingly discredited on a societal level (2004). The second trend involved unwaged women’s labour becoming increasingly expected of women as divides in gendered labour persisted and deepened (2004).

These historical points are significant when examining activism amongst contemporary American witch communities since many of these societal issues that impact women’s lives are still prevalent worldwide (Federici 2004; Sollée 2017). For additional information pertaining to recent increased visibility of witches in the United States, the following articles are suggested as supplementary reading.

Suggested Reading

Emba, Christine. 2018. “An entire generation is losing hope. Enter the witch.” The Washington Post , November 13, 2018.

Yar, Saman. 2018. "Witchcraft in the #MeToo Era." The New York Times, August 16, 2018.

Online Witch Entrepreneurship and Instagram

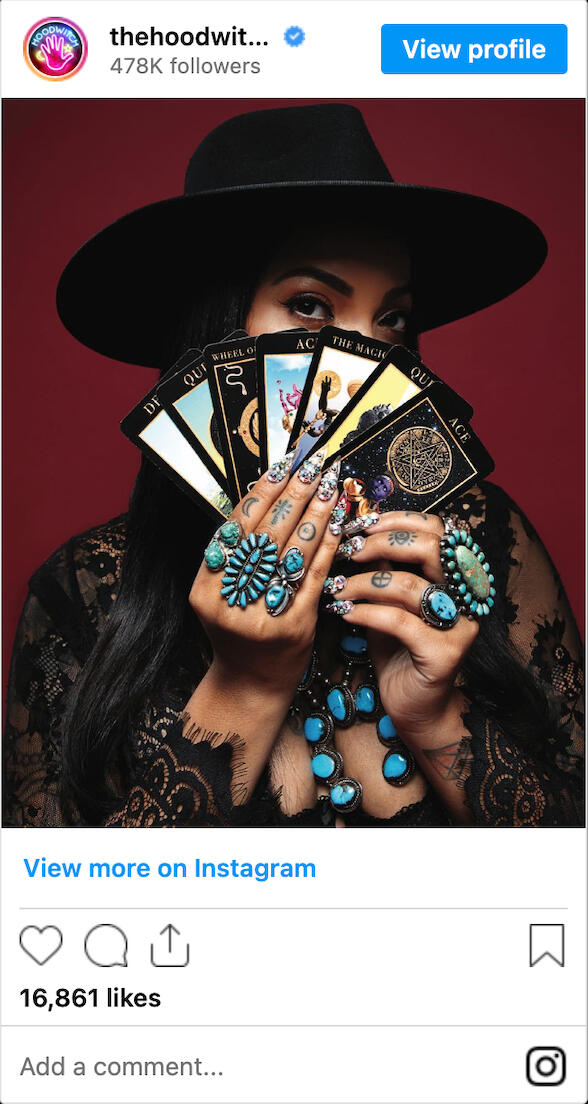

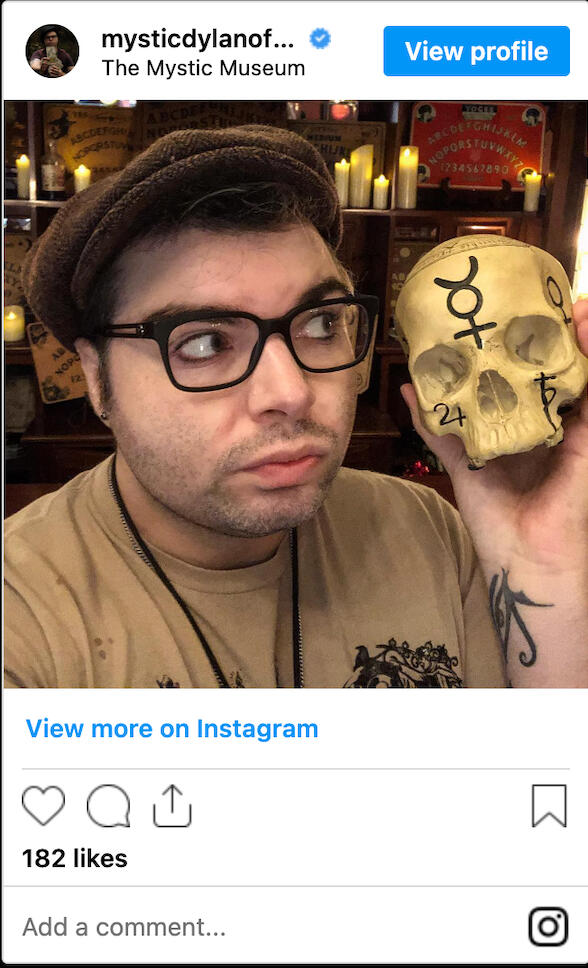

It is not coincidental that the vocations and positions of contemporary witches typically overlap with ones that self-identified witches held throughout history. Entrepreneurial witches are often artists, writers/authors, spiritual healers, advisors, holistic medical practitioners, educators, performers, diviners (for example, Tarot card readers and rune readers), online shopkeepers, and professional spellcasters. Witches are capable of holding more than one of these titles, and often do. This is also not an exhaustive list, as witches do not need to conform to specific guidelines to be witches.

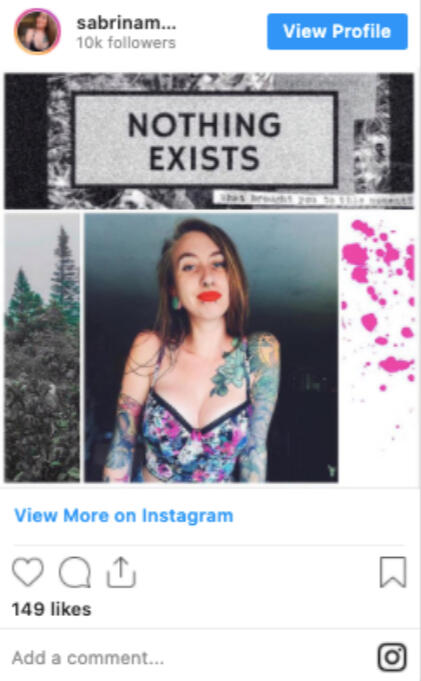

Observing these images, it is easy to recognize that the witching community is very diverse. Witches can be of any gender identities, sexual orientation, race, etc., and inclusivity is key to witch activists (Sollée 2017).It is also important to note that advertising, self-expression, and social activism are synonymous with one another for many of these socially conscious entrepreneurs. This is evident through the content they post on their Instagram profiles. When it comes to the promotion of services and products online, socially conscious witch entrepreneurs share various types of digital content through their Instagram profiles with the most popular types of content being witchcraft-related memes, product images, personal vlog entries, and selfies (as seen in the above selfie posts).

Memes

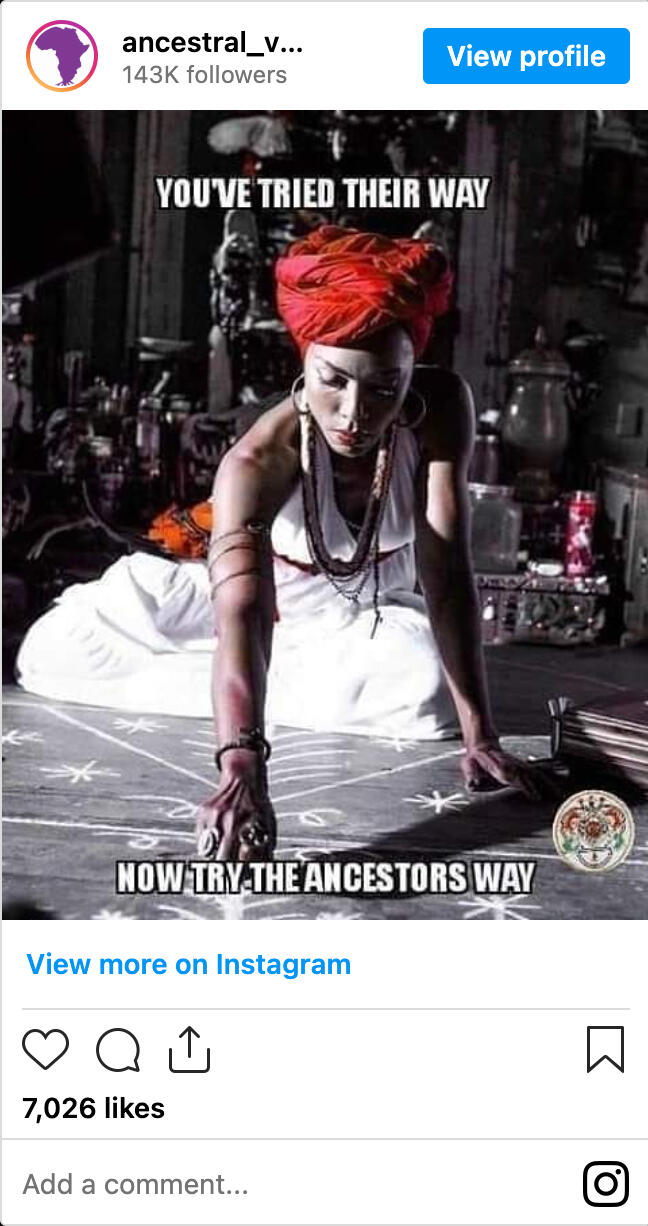

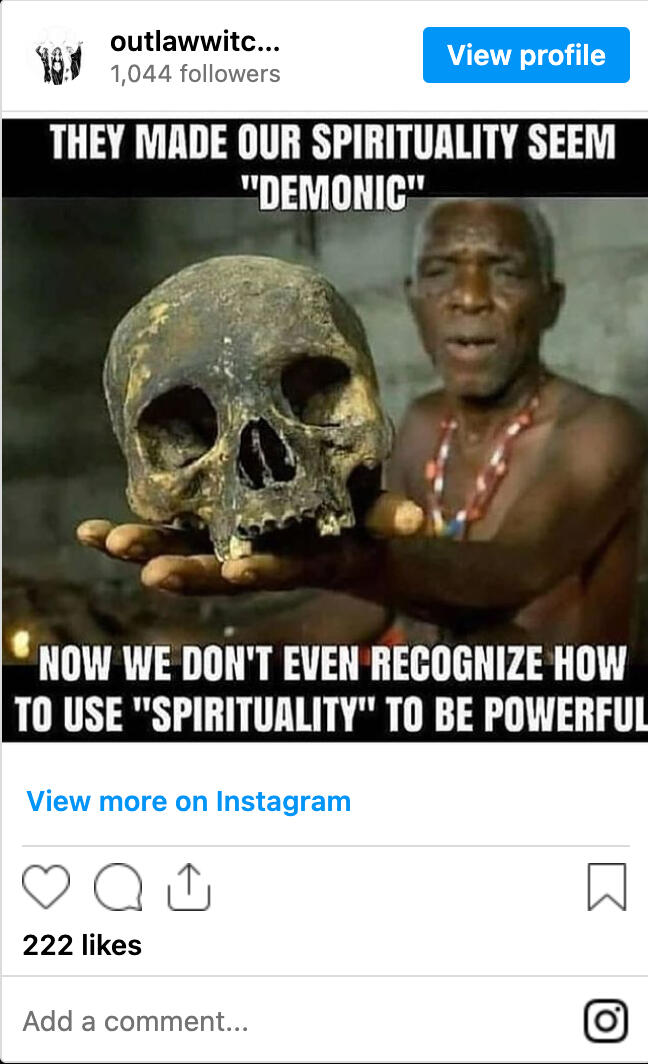

Memes (seen below) are often shared amongst witches to disseminate knowledge and wisdom for a wide range of topics from spells tips and Tarot card spreads to wellness advice. Memes are also used throughout digital witch communities as a ‘social coagulant’ since niched memes disseminate community-related jokes, short musings, and messages pertaining to social activism.

In many ways, these memes act as fluid symbols as they depict older, more recognizable symbols such as pentacles, sigils, Tarot cards, altar items, and images of popular polytheistic deities. This type of symbol making, replication, and dissemination is reminiscent of David Kertzer’s (1988) observations pertaining to the importance of symbols amongst communities. These recognizable symbols are consistently repurposed and reframed in memes, and they continue to encourage engagement and discourse throughout Instagram witch communities due to recognition (1988).Much like Edgar Gómez Cruz and Helen Thornham’s (2015) observations, which pertain to selfies and their intrinsic embedment in public-facing digital communicative processes, it is imperative that all Instagram posts including memes are examined not only for their initial content. The mobility (i.e., shareability) of memes and related subsequent user-generated content (e.g. comments related to memes) are collectively significant components of online interactions. While I cannot elaborate further on the complex nature of this form of digital discourse due to the scope of this project, this area of research is one that I intend on providing further focus on in the future. I also intend on further examining the roles of selfies in digital entrepreneurship since selfies are typically used to provide notable levels of personability and credibility to online businesses in lieu of in-person representation.

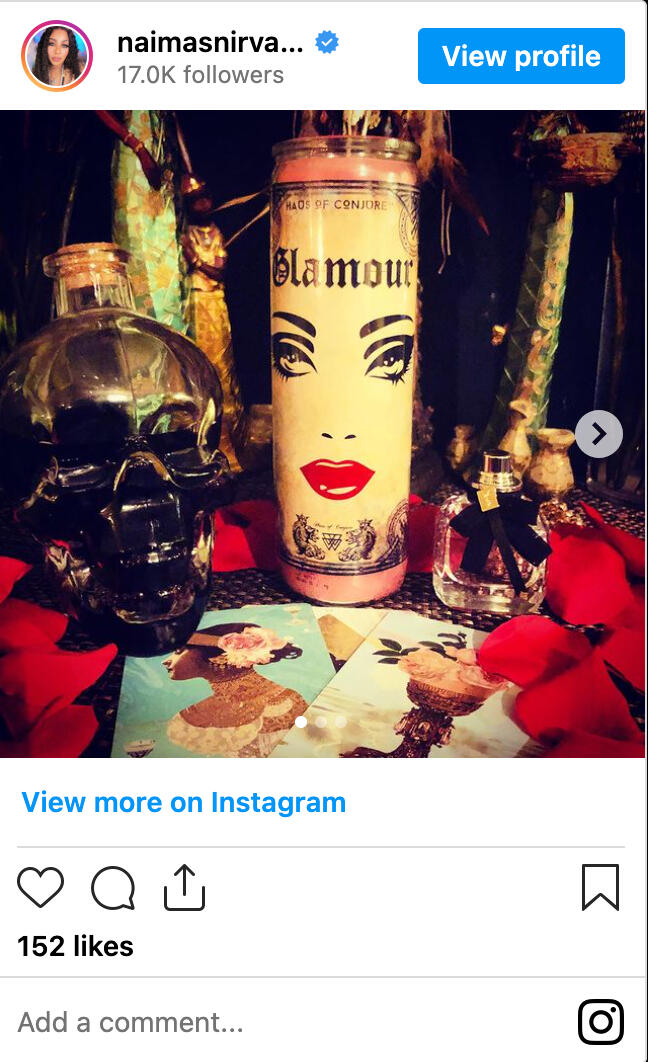

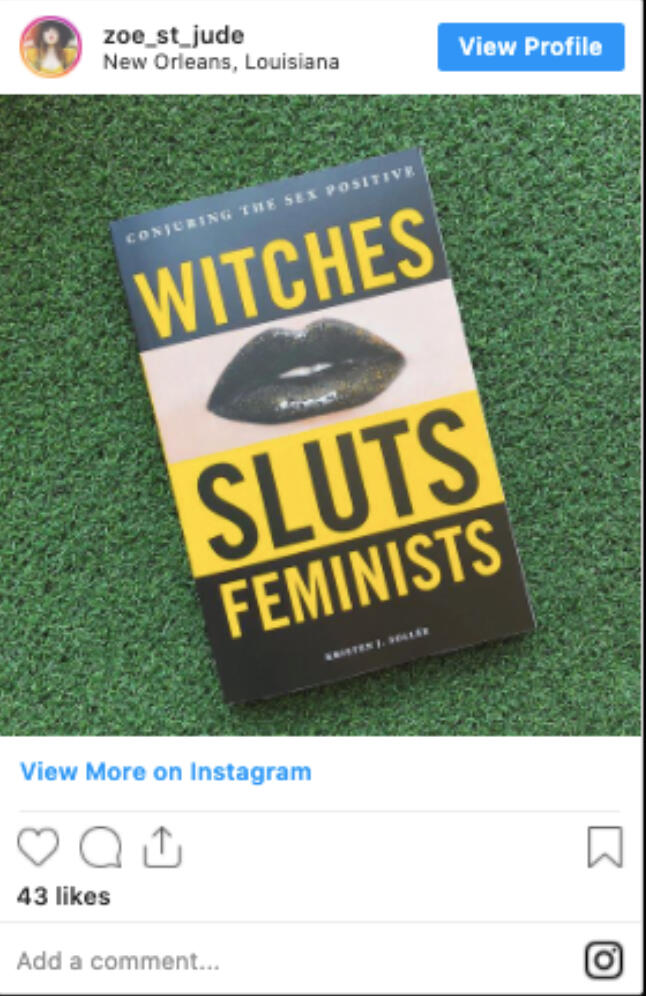

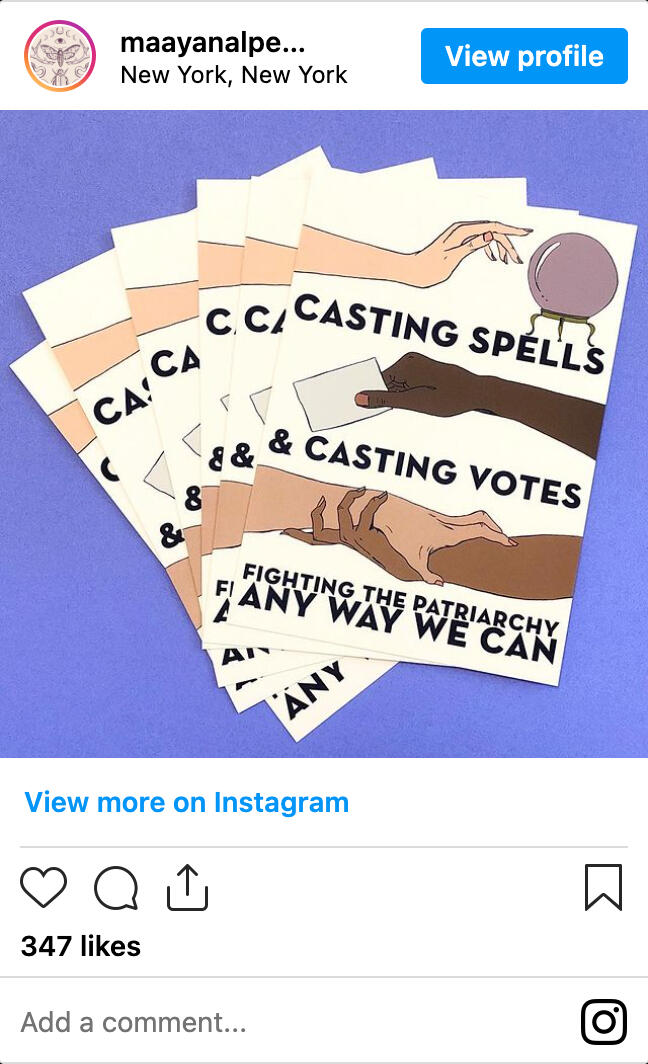

Product Photography

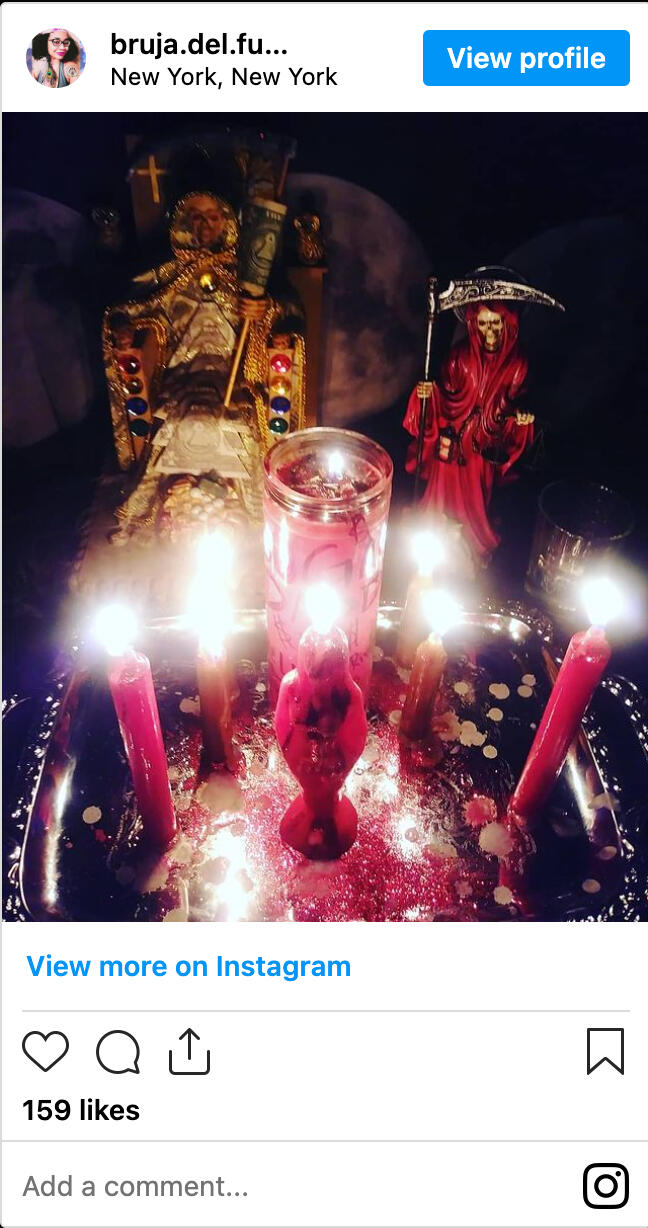

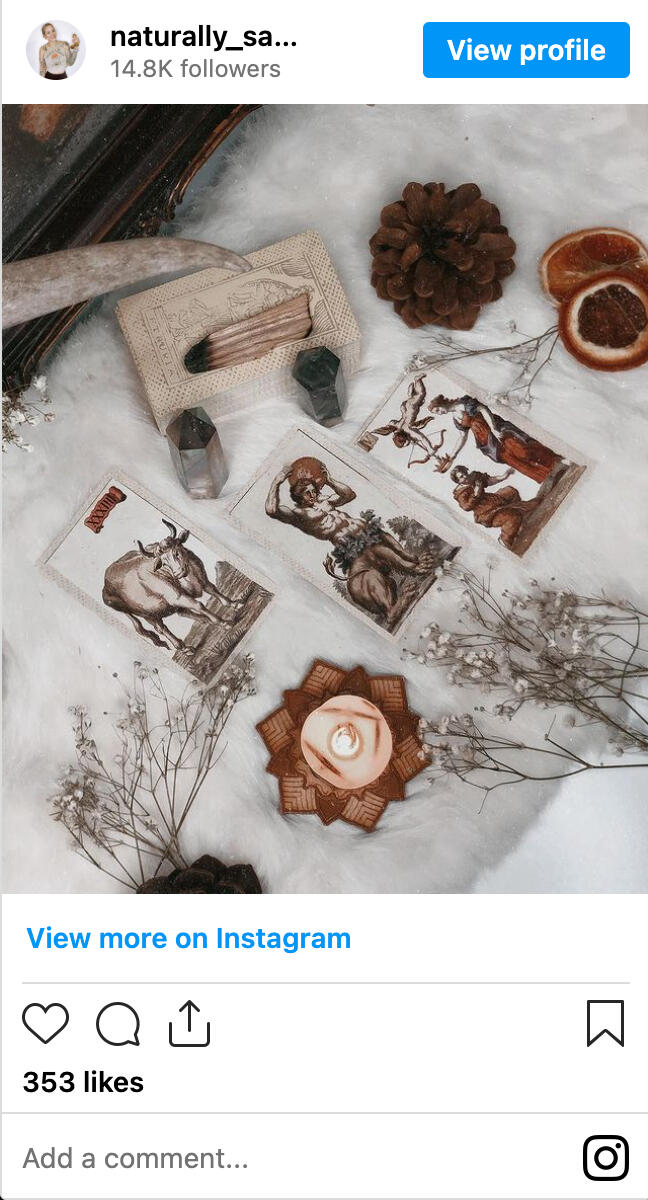

This is a small sample of product images shared by online witch entrepreneurs through their Instagram profiles. Advertised materials include (but are not limited to) ritual and altar supplies, fashion accessories, books, crystals, and artwork. Images of divination tools (e.g. Tarot cards and oracle cards) along with images of personal altars are typically used to promote services such as spellcasting and divination readings. It is common for witch entrepreneurs to pose with their products in selfies and/or other types of images where specific parts of their bodies are prominent such as their hands. They often also cross-promote products from other Instagram users they respect, which bolsters communal ties.

Witches as Socially Conscious Entrepreneurs

Women along with numerous men and non-binary individuals who were tried throughout history as “witches” are recalled when examining the social justice tenets discussed by Kristen J. Sollée (2017) in reference to “witch feminism”. These tenets include a variety of social causes including the promotion of pro-choice movements, non-binary gender rights, intersectional feminism, sex positivity, sex trade positivity, pleasure positivity, body positivity (which includes the decolonization of Eurocentric beauty standards), and the elimination of patriarchal limitations that prevent societal equality (2017).

It is apparent through a variety of Instagram posts that witches advocate for numerous causes and movements including environmental conservation, Black Lives Matters, and decolonization efforts. This intersectionality is unsurprising when considering Trinh T. Minh-Ha’s (1987) observations pertaining to the societal roles and objectives of contemporary feminism:

Hegemony and racism are, therefore, a pressing feminist issue; 'as usual, the impetus comes from the grassroots, activist women's movement'. Feminism, as Barbara Smith defines it, 'is the political theory and practice that struggles to free all women . . . Anything less than this vision of total freedom is not feminism, but merely female self-aggrandizement.' (Minh-Ha, 1987, 12)

In their inclusive spirit, socially conscious witching communities inherently recognize that obstructive capitalistic and patriarchal infrastructures cannot be overcome when related communities are divided or even deprioritized, as noted by Minh-ha (1987).Social activism-related messages are shared through Instagram profiles alongside product images and other digital content (e.g. selfies, videos, etc.) that entrepreneurial witches use to advertise their products and services. At times, their products will even embody these socially conscious messages (seen below). It is evident overall that when an individual supports witch entrepreneurs through purchasing power, they are also supporting that entrepreneur’s social causes and activism.

Symbols associated with contemporary witchcraft including pentagrams, besoms, sigils, smudge stick bundles, and divination tools (e.g. crystal balls) are used in numerous memes and product-related artwork to signal messages of solidarity. This process is akin to the political symbol creation processes David Kertzer (1988) observed amongst nations and their related institutions. Kertzer (1988) recognized that nations are invisible forces which require symbols and rituals to unite their citizens. Since online communities and digital social activists do not meet in physical spaces regularly or, sometimes, at all, community symbolism and even hashtags assist in inspiring and sustaining messages of activism.Sometimes, fashion and make-up become key aesthetic tools in online witch activism (Sollée 2017). This is especially salient amongst socially conscious witches who use Instagram since Instagram is a social media platform that relies on visual content. While witches are encouraged to wear or not wear whatever they please, some witch activists purposefully wear social markers of epitomized or ‘ultra’ femininity (2017). These social markers include bold makeup, clothing, and fashion accessories that are condemned in numerous conservative communities for being “slutty” or sexually explicit (2017). Some witches wear gender neutral attire not only to suit their aesthetic preferences but to also advocate for the rights of non-gender conforming people. Through these acts, witch activists are taking a stand for various social causes such as gender equality, sex-positivity, body-positivity, and self-sovereignty.Although digital activism has been heavily critiqued for its ephemeral nature, as Yarimar Bonilla and Jonathan Rosa (2015) observed in their research on Twitter hashtag activism, digital activism can be a powerful influencer when examining its effects on new and ‘traditional’ news outlets. Political intuitions have been documented for recognizing digital activism movements, and these movements provide a platform to activists who are otherwise unable to protest in-person due to geographical barriers (e.g. communities are widely dispersed) or potential physical dangers (2015).

Sameness

Around the mid-twentieth century, Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer (1944) publicly critiqued what they termed the “culture industry”* for utilizing mass production and mass dissemination to cultivate a level of “sameness” across art and media. Both scholars posited that art and media were being created and disseminated through the culture industry in manners that prioritize advertising as “its elixir of life” (1944, 68) since this industry sustains itself on corporate advertisement funding. The result of this prioritization of corporate funding, according to both scholars, has been a detrimental commoditization of culture that is widely accepted by members of society at the sacrifice of creating quality art and media that does not possess this critiqued crux of “sameness” that results from capital interest (1944).One salient example provided by Adorno and Horkheimer (1944) examined how magazine advertisements are presented by magazine publishers in such a manner that they resemble or even, at times, are superior in aesthetic quality to editorial content. This results in advertisements becoming more conspicuous than editorial content even though readers purchase magazines primarily for their editorial content. This aesthetic prioritization of print advertisements was problematic to both scholars since they felt that art and media content should never be created in manners that take the creative process away from citizens (1944). They also declared that media and art should never be secondary to capital interest or be created merely as vehicles for corporate advertisement campaigns (1944).With the advent of Web 2.0, which has brought with it social media outlets including Instagram, it is evident that people have more control over advertising their businesses and creating their own content, as witnessed through the online presences of prominent social media influencers and small businesses. The capitalistic frameworks of North American societies, nevertheless, still appear to point towards Adorno and Horkheimer’s arguments pertaining to corporate advertisement prioritization and “sameness.”Just as Safiya Umoja Noble (2018) observed in her work pertaining to algorithmic biases embedded in Google search results, it is clear that biases in the curation of search results and even Instagram hashtag feeds are being perpetuated through flawed machine learning processes. These flaws result in the selection of certain images for curation due to their resemblance of images that were preselected by programmers to train these curating algorithms. As Noble (2018) notes, however, it is not the algorithms’ responsibility to change. It is the programmers who are responsible for creating, maintaining, and training these algorithms who must recognize the detrimental social repercussions of such biases in order to resolve the related issues at hand.Noble (2018) concluded that the biases she recognized in Google search engine results resulted largely from corporate interest. Corporate paid content (i.e., content certain companies paid Google, Inc. to advertise on their behalf) appears closer to the top (if not at the top) of Google search engine results (2018). Similarly, with regard to Instagram hashtag feeds, the sameness Adorno and Horkheimer (1944) criticized the “culture industry” for is prevalent in Instagram hashtag feed curation. This is largely due to corporate advertisement campaigns along with the aforementioned issues and unaddressed biases in machine learning processes. In 2018 alone, it was estimated that Instagram grossed $5.48 billion in net advertisement revenue; indicating that corporate advertising is a crucial revenue stream for Instagram (Condliffe 2018).

* The “culture industry” was centred mainly around film, television, radio, and magazines in Adorno and Horkheimer’s (1944) essay. They criticized this industry both for “confin[ing] itself to standardization and mass production and sacrific[ing] what once distinguished the logic of the work from that of society” (1944, 42).

Algorithmic Homogeneity

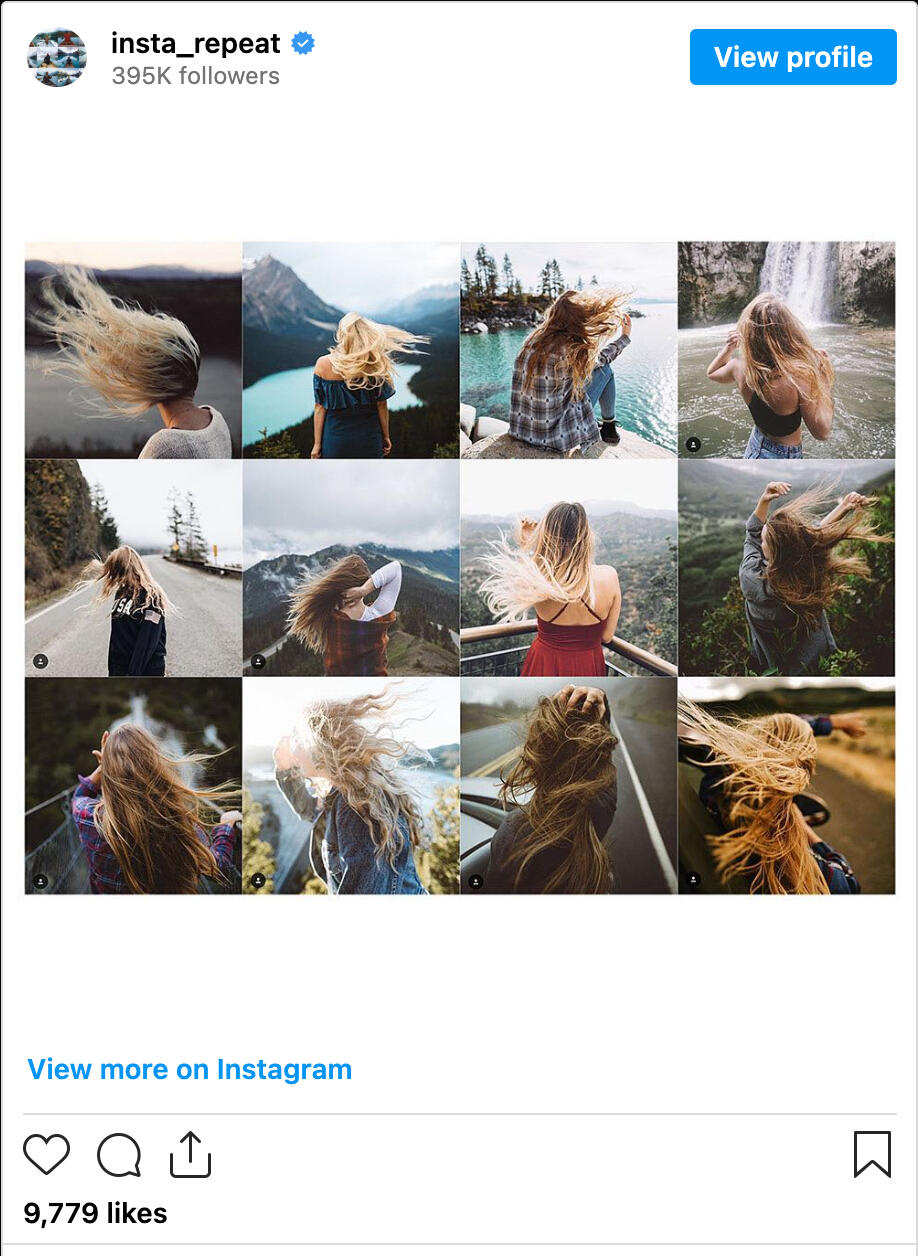

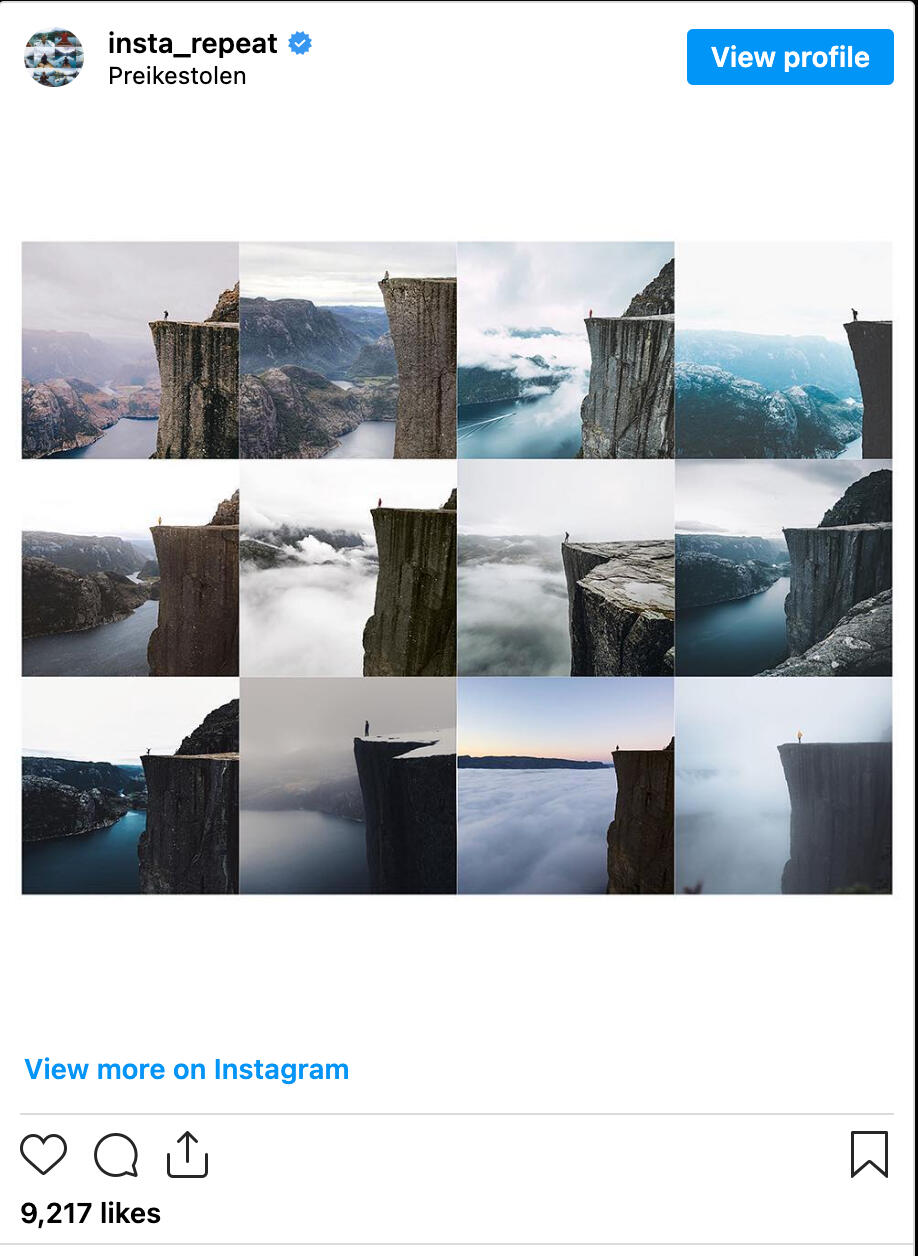

While numerous scholars and technology journalists have observed and criticized Instagram for perpetuating a salient level of problematic, homogeneous algorithmic curation, one Instagram account in particular, “@insta_repeat”, provides key visual representations of this practice. @insta_repeat posts a series of popular Instagram posts depicting the same travel destinations from the exact same angles (Shamsian 2018). In some instances, the destinations appear to be different but the landscapes, objects and/or people in these popular Instagram posts bear specific similarities.

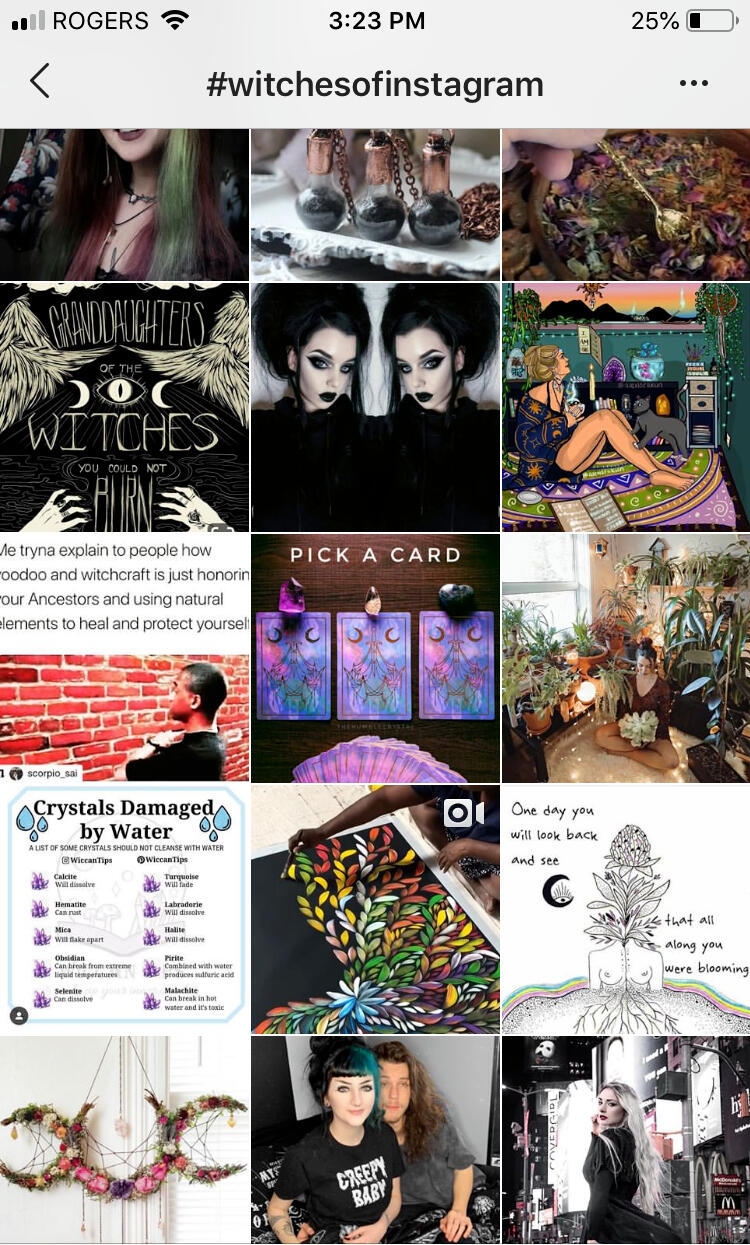

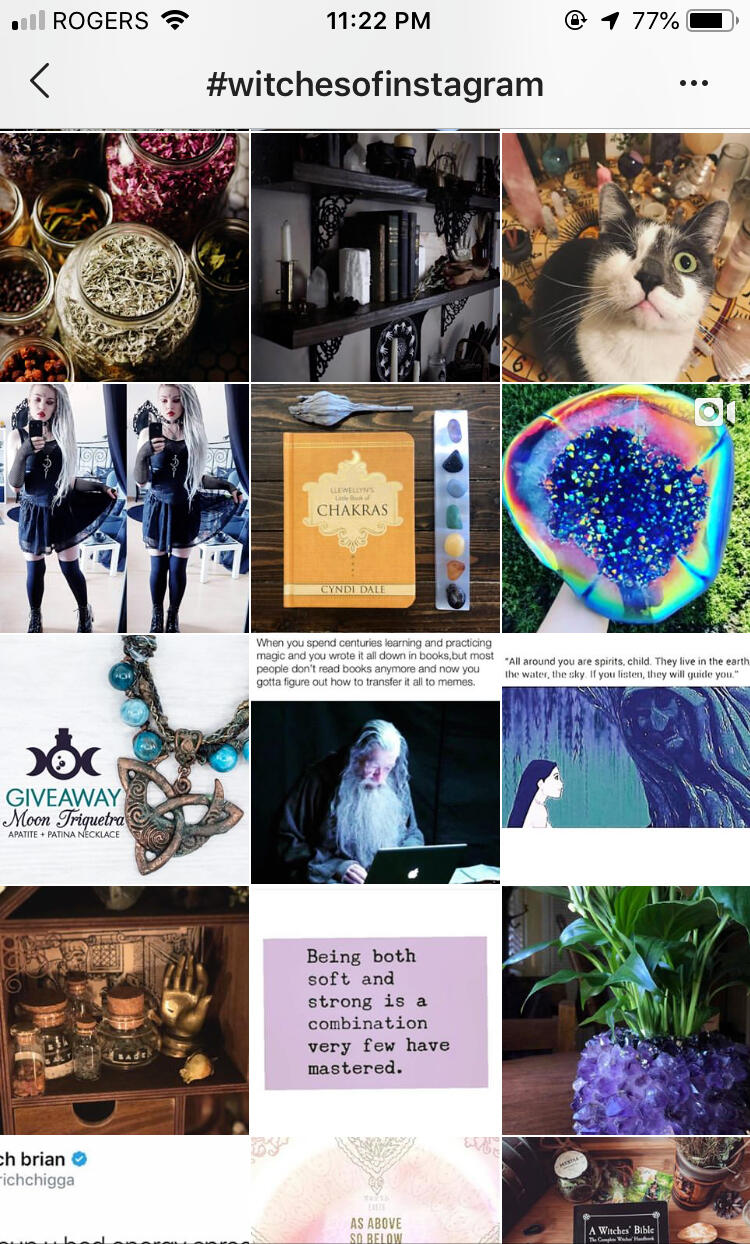

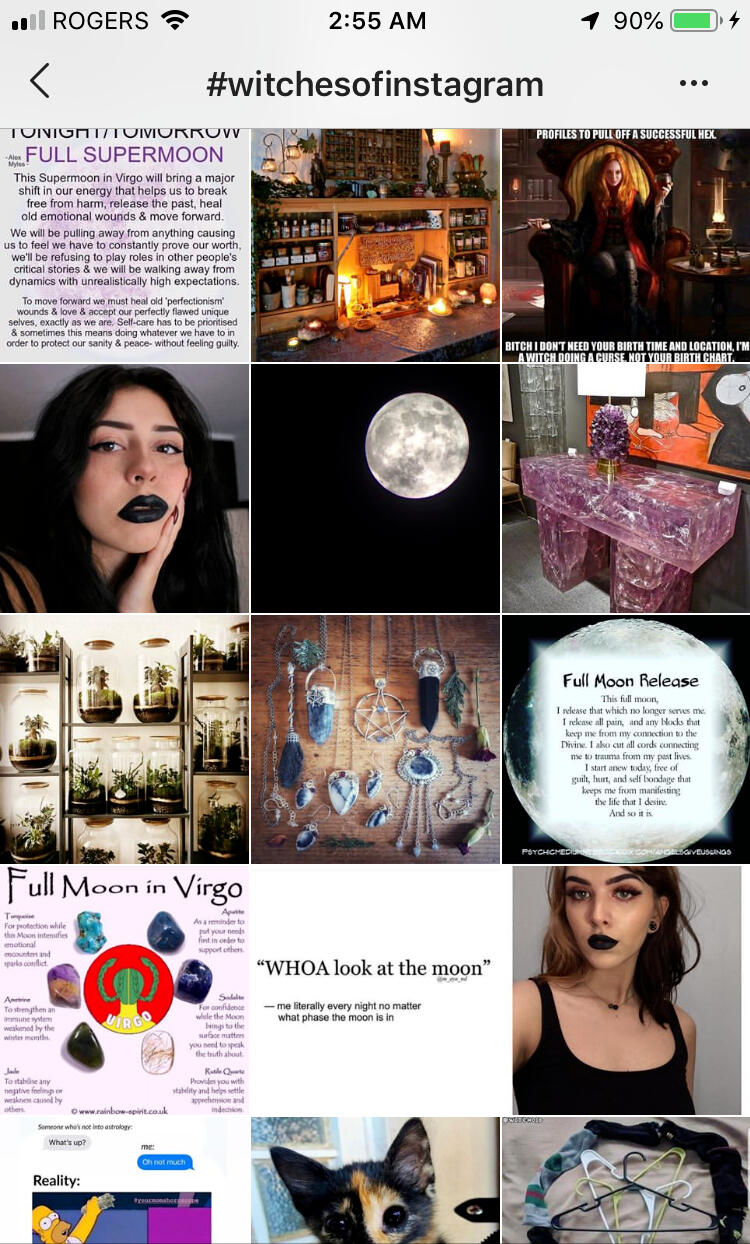

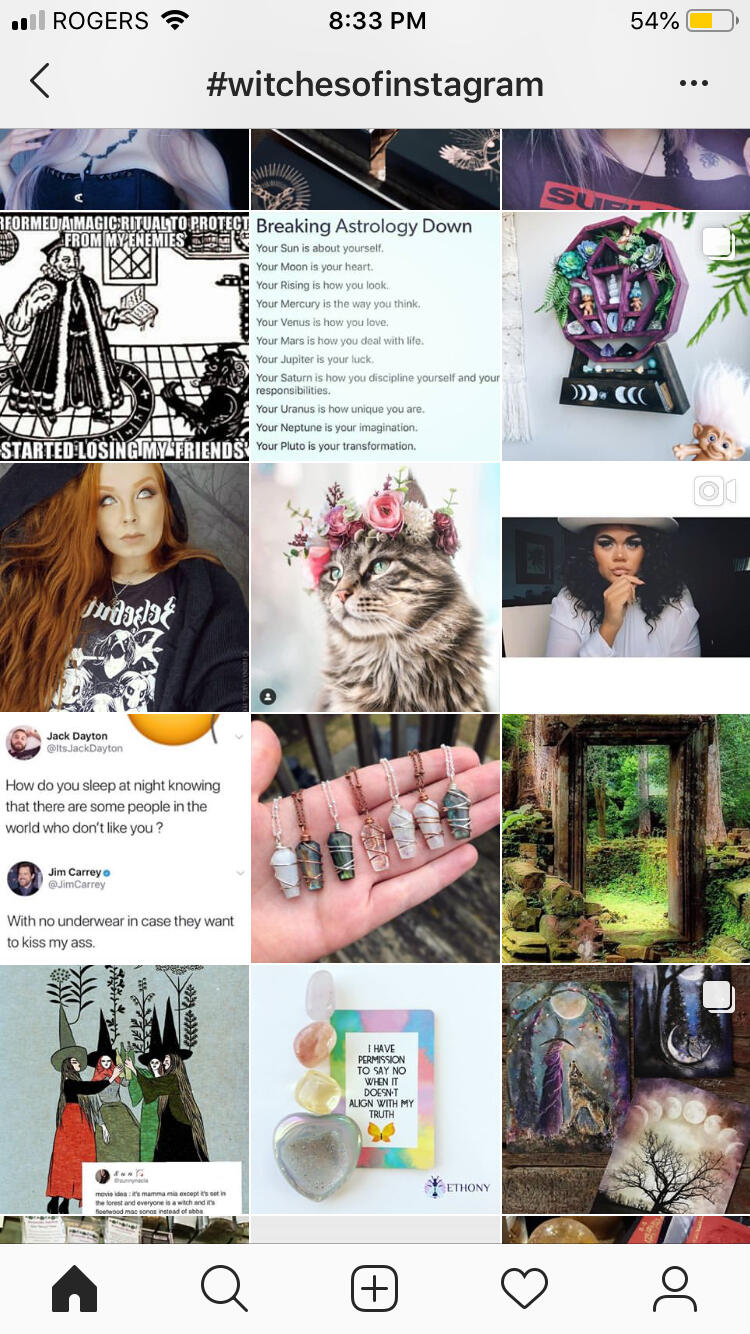

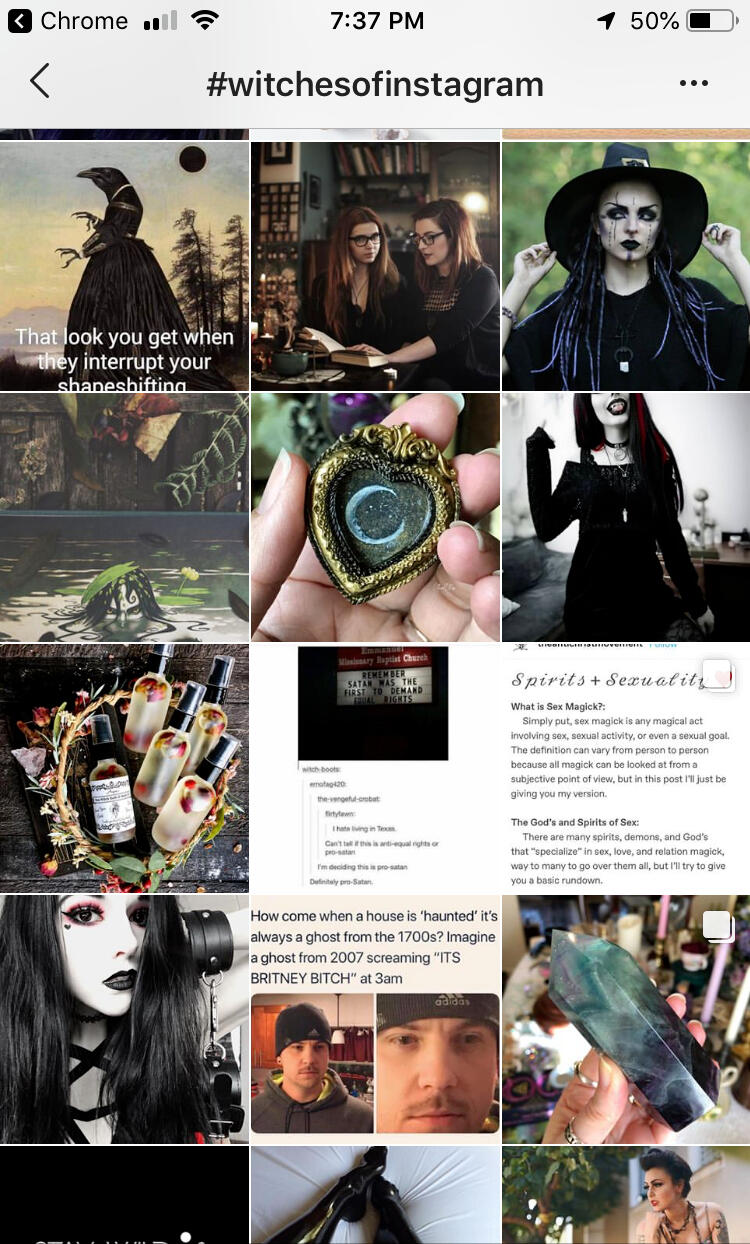

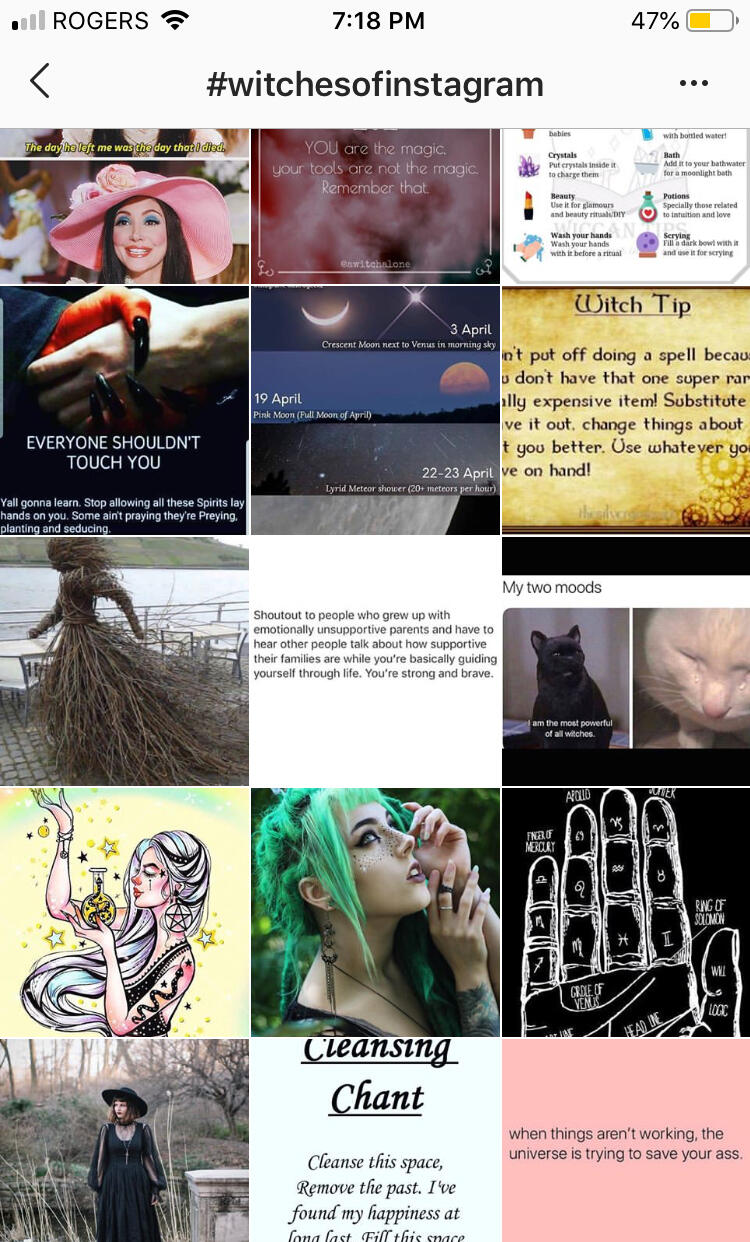

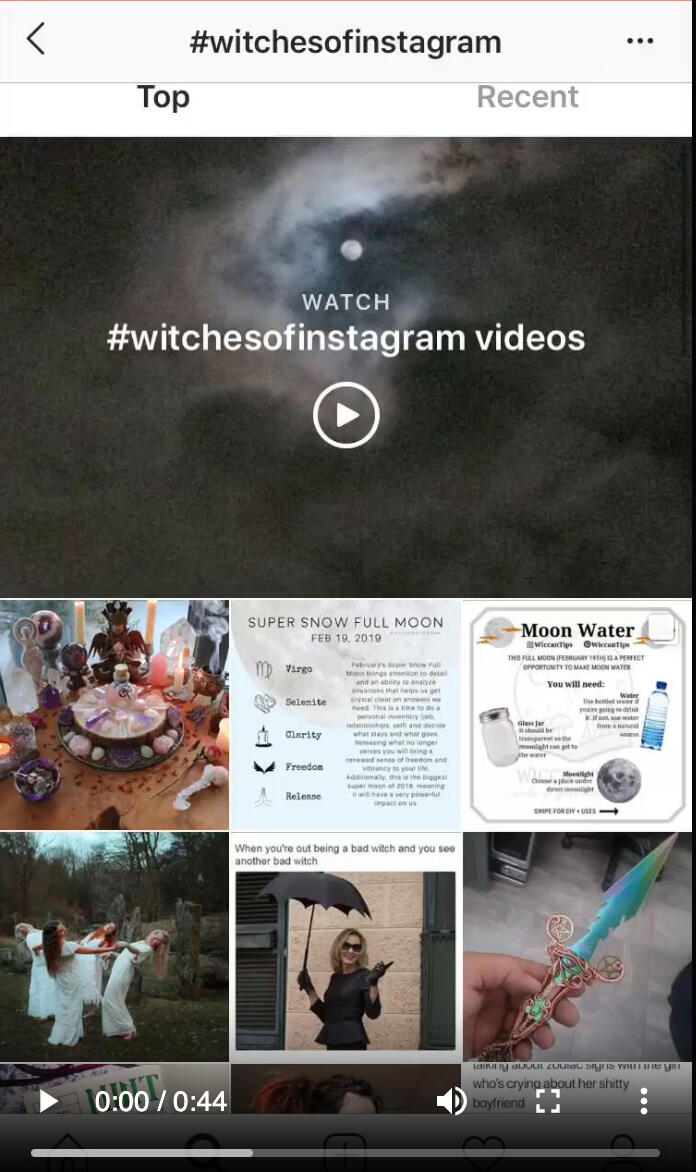

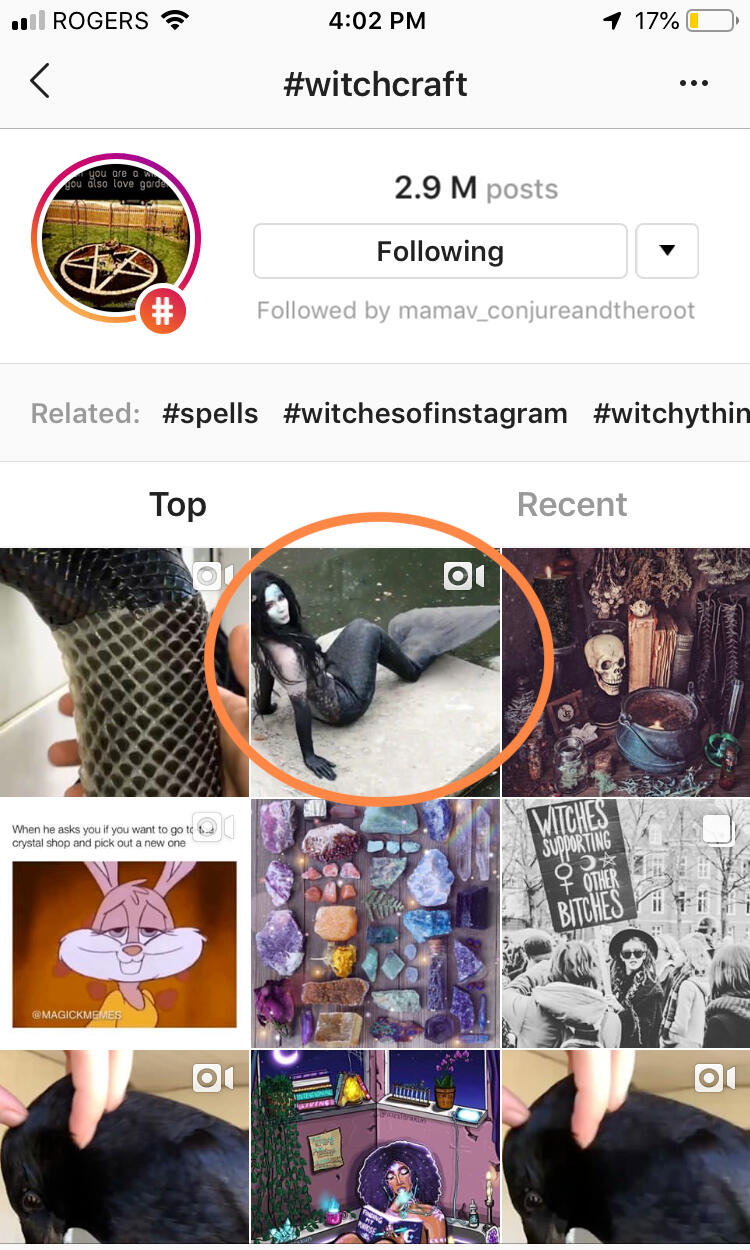

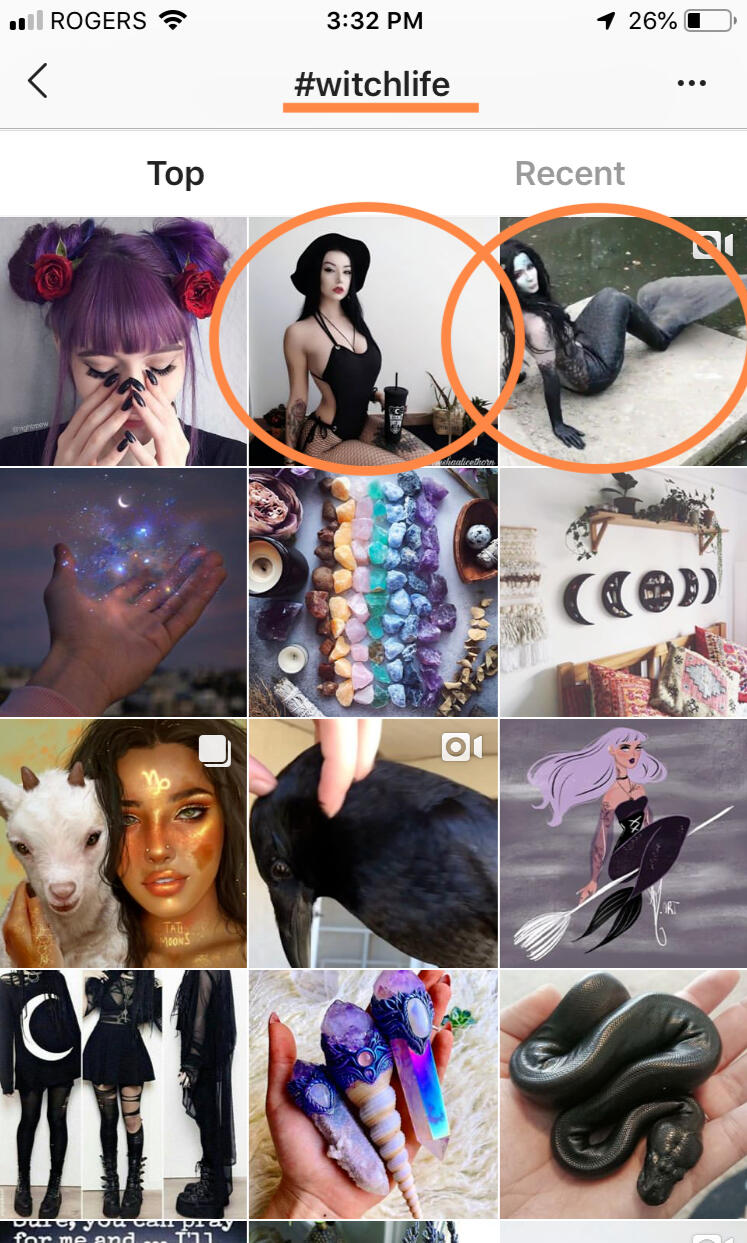

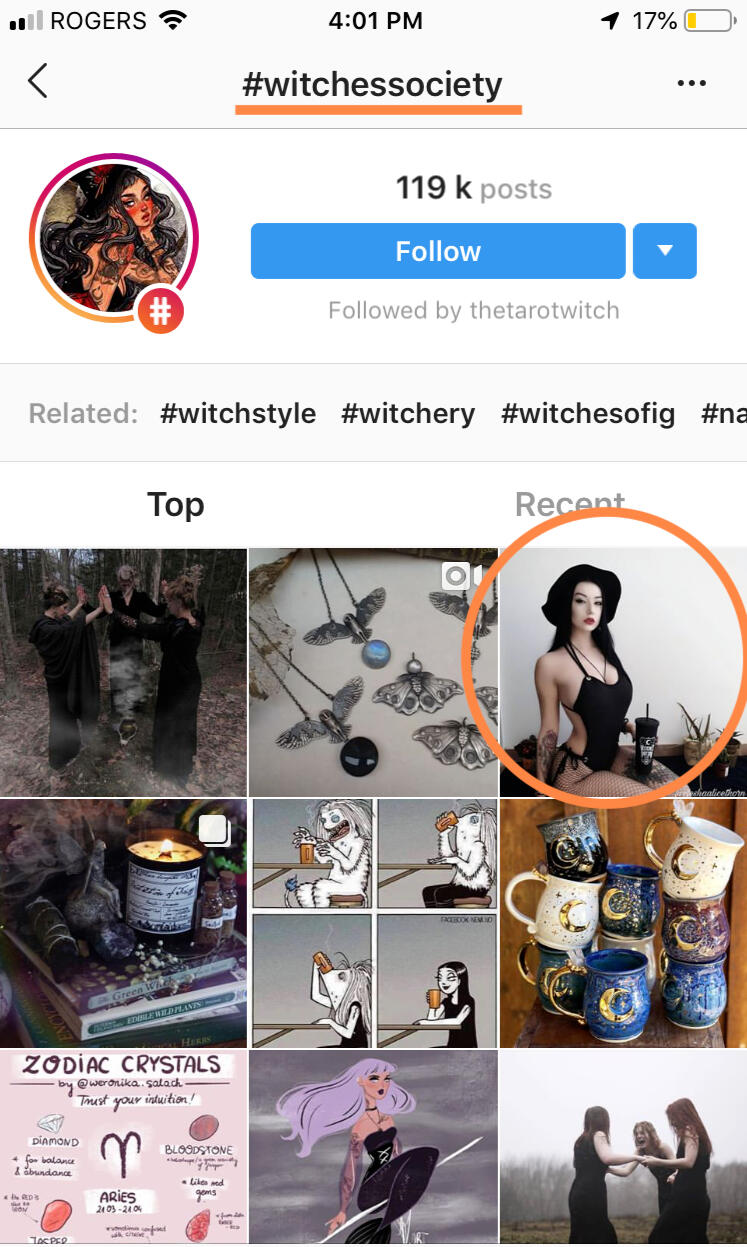

Based on Noble’s (2018) observations on how deep learning for machine learning algorithms (i.e. artificial intelligence) yields narrow curation results based on narrowly selected training values, I posit that popular Instagram posts like the ones shown on @insta_repeat bear certain similarities that enable Instagram’s algorithms to verify that they depict what they claim to depict. As a result, these images become ‘safe’ and ‘ideal’ images that are considered suitable for promoting/endorsing across Instagram through popular streams such as hashtag feeds. The same is observed in the following screenshots from the Instagram hashtag feed for #witchesofinstagram. It is overall difficult to form concise theories about algorithmic curation since algorithms are proprietary information. Nevertheless, it is still possible to analyze the curation patterns of algorithmic output.

Mobile phone screenshots from the Instagram hashtag feed for the hashtag #witchesofinstagram. Screenshots created by author.

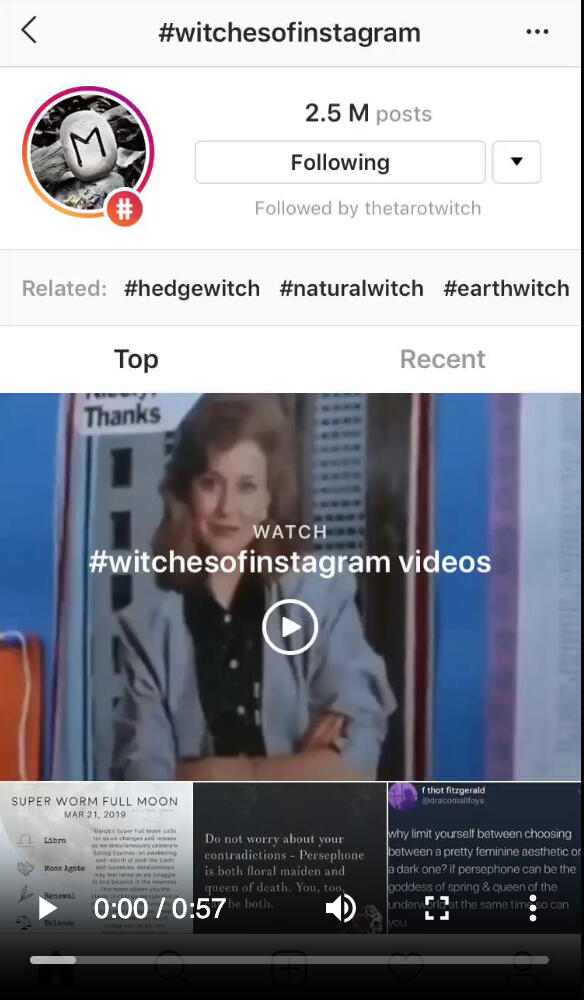

These screenshots and videos of Instagram’s #witchesofinstagram hashtag feed were taken over several days. It is apparent that the diverse population of the American witch community is not adequately represented in the selfies that are algorithmically selected for this hashtag feed’s curation. Moreover, activism-related posts along with ritual-related images from non-Eurocentric spiritual traditions (e.g. altar images from brujas or Hoodoo rootworkers) are sparse, albeit a few divination-related product shots. Both trends are puzzling since Instagram posts that fit these descriptions are frequently tagged with the hashtag #witchesofinstagram.

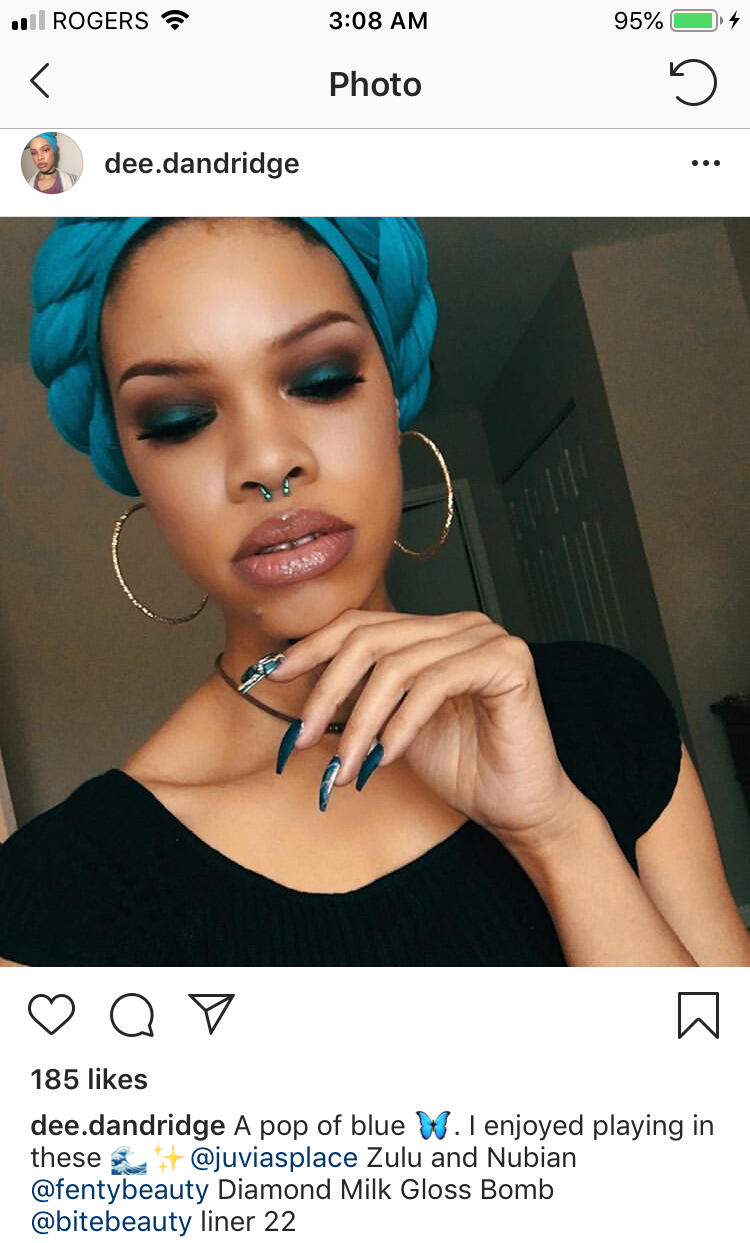

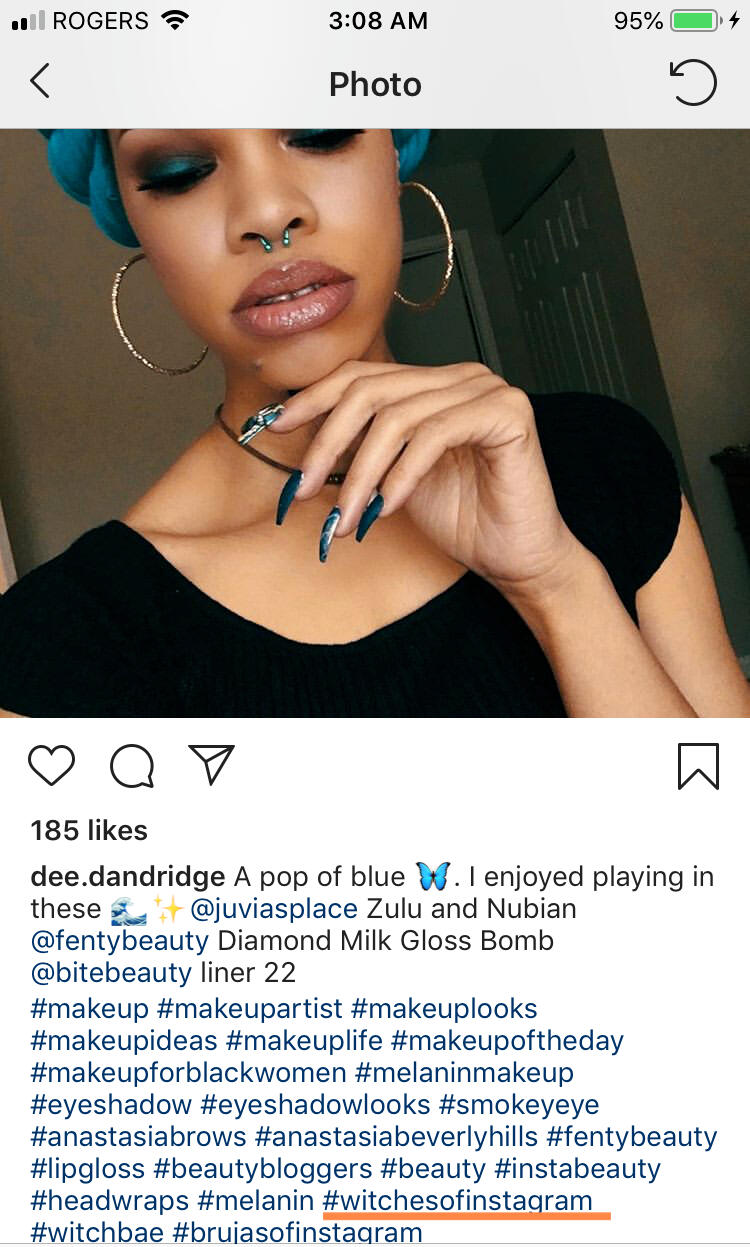

Below are screenshots of Instagram posts that possess the #witchesofinstagram hashtag but were not selected for #witchesofinstagram hashtag feed curation.

Left images depict an Instagram post that maintains the #witchesofinstagram hashtag. It was recently posted at the time these screenshots were taken. The third image depicts that this Instagram post was selected for the #brujasofinstagram hashtag feed. The video on the right displays that this Instagram post was not selected for the #witchesofinstagram hashtag feed. While Instagram hashtags feeds do not always feature posts in a purely chronological order, I scrolled down far enough in the above video to a section in the feed where older posts from 1-2 days ago would appear. Screen captures created by author.

Left images depict an Instagram post that maintains the #witchesofinstagram hashtag. It was posted an hour before these screenshots and the corresponding video were produced. The video on the right displays that this Instagram post was not selected for the #witchesofinstagram hashtag feed. While Instagram hashtags feeds do not always feature posts in a purely chronological order, I scrolled down far enough in the above video to a section in the feed where older posts from 1-2 days ago would appear. Screen captures created by author.

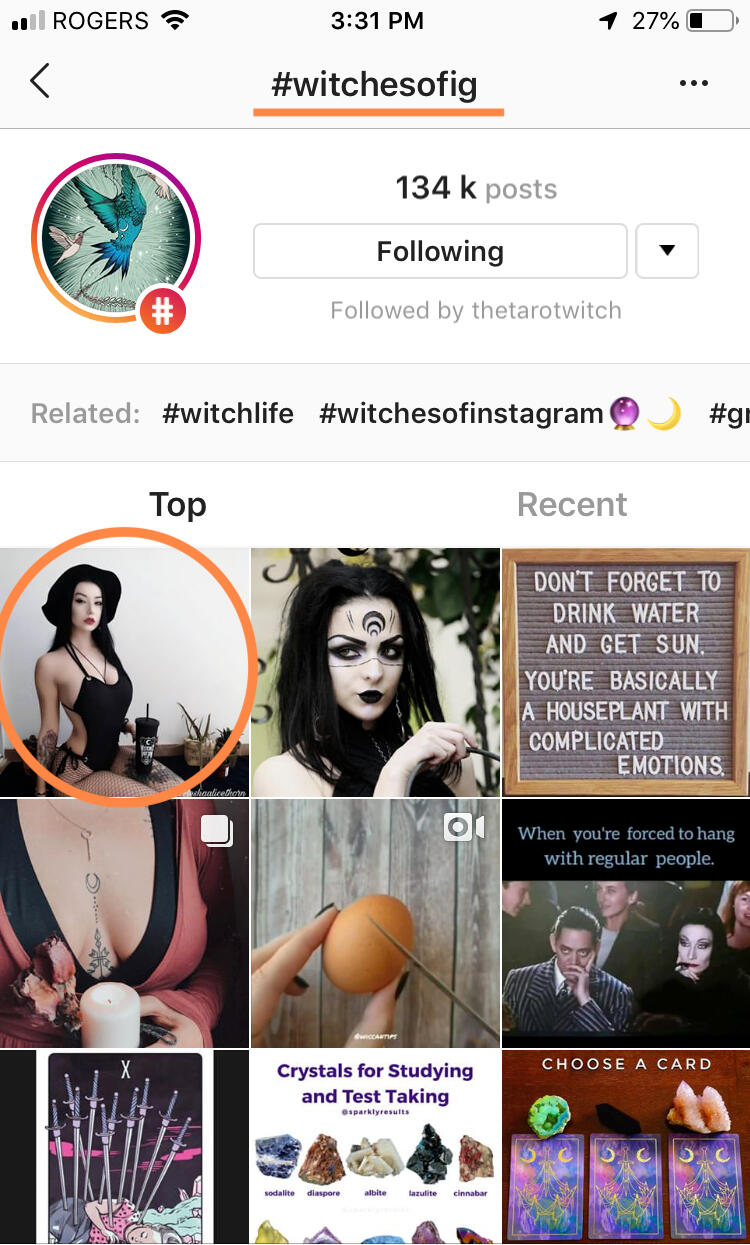

It could be argued that Instagram posts are selected to be featured in only one hashtag feed even if a post bears multiple hashtags. This would be difficult to verify since algorithms are proprietary information. Nevertheless, as seen in the above images, the Instagram posts circled in the first two screenshots appear in multiple hashtag feeds simultaneously. As seen in this series of screenshots, the hashtag feeds depicted are for the following popular witch-oriented hashtags: #witchesofig, #witchcraft, #witchlife and, #witchessociety. Screenshots created by author.

I am unable to provide all of the collected data pertaining to these trends within the scope of this project but the following findings were apparent throughout my research: witches of colour were often featured through hashtag feeds related to ethnicity and colour including #brujasofinstagram and #witchesofcolor. People of colour including celebrities like Beyoncé were more likely to appear in the #witchesofinstagram hashtag feed if they were depicted in memes (i.e., depicted with text and sometimes a frame around their image). People of colour were also featured in this hashtag feed predominantly through illustrated depictions of people of colour. Based on the collected data, these trends also appeared to apply to people who did not fit Eurocentric and/or ableist beauty standards.Overall, as observed in the provided screenshots and videos, people who fit the following criteria had their selfies/photographs selected and promoted more often through the #witchesofhashtag feed (versus being subjected to primary representation through artistic renderings and memes): appear ‘feminine’ within a heteronormative scope (i.e., cisgender women), Caucasian-passing/European facial features and hair types, of slim body types, and wearing black/gothic-inspired makeup and clothing in their photographs.In addition to these trends, some of the selfies featured through the #witchesofinstagram hashtag feed are tagged with the #witchesofinstagram hashtag by other users despite the fact that the Instagram models depicted in these images do not necessarily identify as witches. While this is acceptable as long as these models do not object to this, it is still worth questioning why a more diverse range of witches are not represented in popular witch-related hashtag feeds including the #witchesofinstagram hashtag feed.

”

For the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change'.

(Audre Lorde as cited in Minh-Ha 1987, 5)

Some may argue that social media platforms bear no responsibility to prioritize diversity and meaningful community representation over their corporate interests. Would this mean then that communities would need to try to beat the “master” at their own “game” if social media platforms are not willing to make necessary revisions? For example, would witches on Instagram need to discover ways to inspire additional community members to use certain hashtags like #witchesofinstagram? In doing so, would this even alter the current algorithmic curation patterns that have been observed throughout this project?It may also be argued that members of the witch community who are not algorithmically prioritized for Instagram hashtag feed curation should promote themselves across other platforms, which is already a common practice amongst social media content creators. However, similar algorithmic biases towards certain body types, aesthetic features, etc. just as readily exist across other platforms. Paying for social media advertising is not always effective either since small businesses cannot compete with the sizeable advertising budgets of large corporations.While no one solution could be offered at this time to circumvent these catch-22 scenarios, it is evident that algorithmic biases obstruct the authentic representation of smaller communities and individuals when it comes to technosocial frameworks. This lack of authentic representation is particularly paradoxical in relation to witch activists on Instagram since their socially conscious messages are buried by the homogeneity they collectively advocate against.The future remains unclear in relation to how technology companies intend on addressing algorithmic biases and to what extent. Nevertheless, as a large body of scholarship continues to grow that addresses the problematic implications of these biases, it will be crucial for anthropologists to contribute to these discussions with their own contextualized ethnographic findings.

What's next?

The purpose of providing these findings through a digital project is to enable people to engage and interact with the Instagram posts and other media that have been embedded and presented throughout this project.Digital anthropology poses its own dynamic, unique challenges and insights due to the fluid state of the World Wide Web. These new circumstances especially highlight why it is significant for anthropologists now more than ever before to use their unique expertise and skill sets to conduct ethnographic research in digital communities. It is evident through this and other digital anthropological essays that there is ample (virtual) ground to cover when considering the online mobility and representation of small digital communities including online witch communities. Additional research is crucial in examining how technosocial frameworks such as Instagram promote, alter, and even even suppress the online representations of certain people and communities.Regarding future research considerations, I draw on Yarimar Bonilla and Jonathan Rosa’s (2015) findings when I consider the significance of venturing beyond hashtag representation on one specific platform in order to examine the mobility, longevity, and use of similar witch-centric hashtags on other platforms. As Nancy A. Van House underscores, “[T]he structure and policies of certain platforms, along with user practices and norms, support and even encourage certain kinds of self-representation, relationships, and even subjects or selves, while discouraging or making difficult others” (as cited in Cruz and Thornham 2015, 5).Thus, it would be prudent to examine how similar non-Instagram-specific hashtags like #witch and #bruja are represented through other platforms including Twitter and Facebook. In the same vein, to further comprehend the significant roles of witch entrepreneurship in contemporary American witch communities, it would be beneficial to examine related online community forums while observing and comprehending other forms of digital community building amongst these communities. In order to conduct this research, ethical permission would be sought through the appropriate academic channels.

Contact

Questions pertaining to this digital ethnographic project could be directed to

devika.singh [at] mail.utoronto.ca